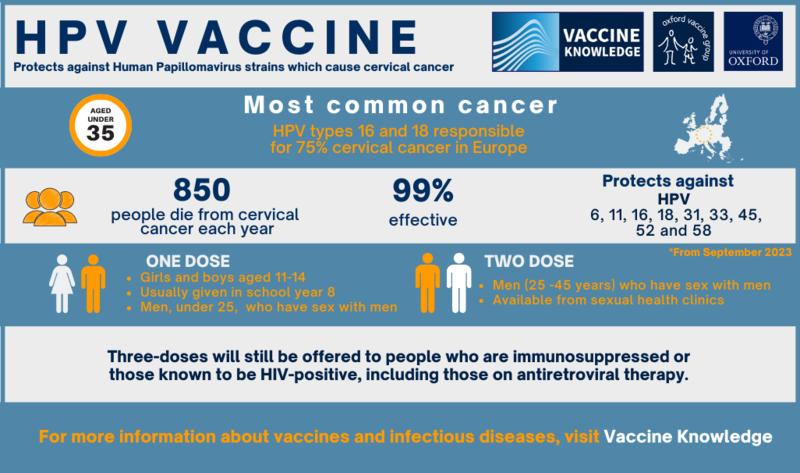

JCVI advises changing from a two-dose schedule to a one-dose schedule.

The JCVI has been examining the evidence of changing to a one-dose schedule for the HPV vaccine since 2018 – the first major review took place in 2020. Following studies in various countries, the evidence has shown that a single dose has comparable efficacy (how well the vaccine works) to three doses.

The JCVI has now recommended this change to the UK government for the routine adolescent programme and MSM programme before the 25th birthday. This change began in September 2023. MSM ages 25-45 still receive two-doses, and individuals who are immunosuppressed or HIV-positive will remain on a three-dose schedule. See the UKHSA report here.

Types of HPV vaccine

There are three HPV vaccines available;

- Cervarix, protects against two types of HPV - 16 and 18.

- Gardasil, protects against four types of HPV – 6, 11, 16, and 18

- Gardasil 9, protects against nine types of HPV - 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58

In the UK, Gardasil 9 is available and offered for free as part of the NHS programme.

All of the vaccines protect against the two most common high-risk types of the virus: 16 and 18. These two strains are linked to over 70% of cervical cancers and 63% of penile cancers as well as most mouth, anus and throat cancers.

In addition to types 16 and 18, Gardasil protects against types 6 and 11, responsible for around 90% of genital warts.

Gardasil 9 protects against a further four types of HPV: 31, 33, 45, and 52 which cause an additional 15% of cervical cancers.

The Cervarix vaccine was previously used in the UK until 2012 and is also used in other countries.

Changing from a three-dose schedule to a two-dose schedule

In May 2020, the JCVI (Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation) HPV sub-committee agreed that the schedule for those aged over 15 years should change from three doses to two doses given at least six months apart. Based on this, the JCVI main committee advised the move to a two-dose schedule at least six months apart, for both those aged 15 years and over, and MSM.

The JCVI also advised (in June 2021) that the three-dose schedule should continue to be offered to individuals who are known to be HIV-infected, including those on antiretroviral therapy, or are known to be immunocompromised at the time of immunisation.

The impact of the HPV vaccine

In clinical trials, the HPV vaccine was over 99% effective at preventing pre-cancer caused by HPV types 16 or 18 in young women, which are linked to 70% of cervical cancers. It is estimated that by 2058, after 50 years of this vaccination programme, 64,000 cervical cancers and 50,000 other cancers will have been prevented.

A 2021 study published in The Lancet has shown that the HPV vaccine has dramatically reduced cervical cancer rates by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at ages 12 to 13. Their findings show that the vaccines have almost eliminated cervical cancer in women born since September 1, 1995.

The World Health Organization has declared a global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer completely through vaccination and screening. It is important that women who have been vaccinated continue to take up the offer of cervical smear testing later in life so that other kinds of cervical cancer can be picked up.

HPV vaccine programmes around the world are currently being evaluated. Evidence from a recent study of 66 million young men and women showed an 83% reduction in high-risk HPV in teenage girls and 66% reduction in women aged 20-24. The study also showed precancerous cervical lesions declined by 51% in teenage girls and 31% in women up to age 24 (Analysis of HPV Vaccine Effectiveness).

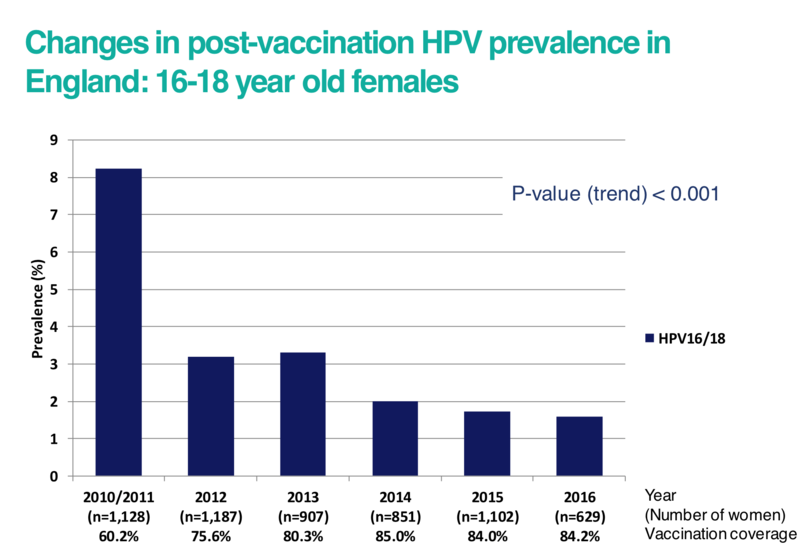

In the graph below, the prevalence of high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 has reduced with the increasing number of women who have received the vaccine in England. Studies have shown that protection against HPV lasts at least 10 years, and this is expected to be long-term.

Click here for an accessible text version of this graph

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673619302983

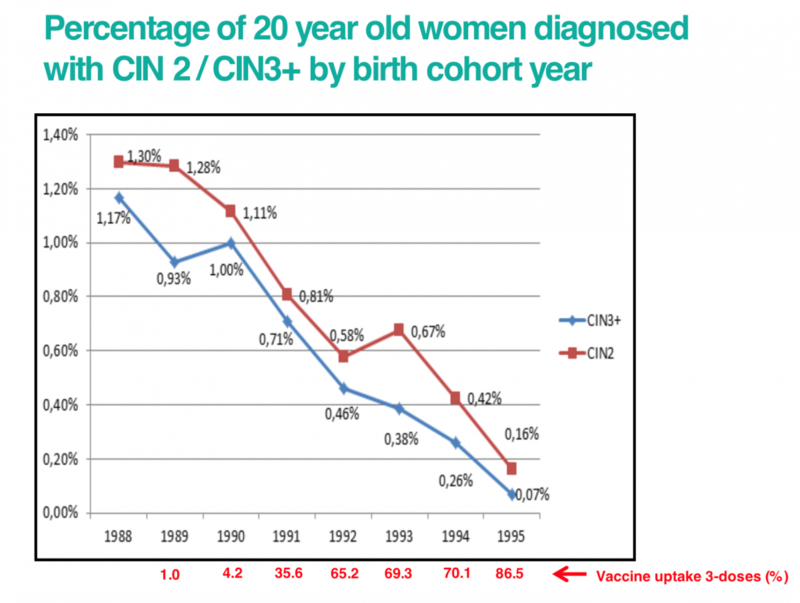

As the HPV vaccine is still new, we won’t know the effect on rates of cervical cancer until those women who have received the vaccine are older. However, studies looking at the percentage of women diagnosed with cervical abnormalities have shown a marked reduction since the introduction of the vaccination programme.

The graph below shows the percentage of 20 year old women diagnosed with cervical abnormalities by their birth year. This shows that as vaccine uptake has increased with each birth year, cervical abnormalities have fallen.

Click here for an accessible text version of this graph

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673619302983

|